This is a huge subject. I will only touch on it here.

In an ethical society a person's freedom should only be limited in so far as the actions of that person impacts on other sentient beings.

| |

The view from near the top of Saint Mary Peak

|

|---|

| This photo was taken from the old path to the Peak. It was bypassed around 1990.

|

|

|

|

|

Many Muslims think it is sinful for a woman to dress immodestly and to eat pork. Jews believe it is sinful to work on the Sabbath and to eat pork. Some Australian Aborigines (First Nations people if you prefer) seem to believe that to go to certain areas will offend the spirits.

Some Christians think that our lives are given to us by God and only God has the right to take our lives. In Australia these people are attempting to force all Australians to live by their beliefs. If these people wish to die miserably, in pain and without dignity, they have a right to do so, but they have no right to stop me from dying when I choose to.

All these beliefs are baseless and delusional. How much should we feel bound to curtail our freedoms due to the delusions of others?

| |

Many of our actions do impact on others. Flying results in the release of large amounts of greenhouse gasses and greenhouse gasses impact all life on earth. Driving cars results in the release of greenhouse CO

2. Should our freedom to fly and drive be limited?

In Australia it has been made illegal to climb

Uluru (Eyre's Rock). The primary justification for this is that it is against the wishes of the traditional owners who say they believe that climbing the rock will offend the spirits. (A more practical and justifiable reason for not allowing the climbing is that there are no toilets on top and urinating and dedicating on the rock will contaminate the waterholes at the base.)

I have written a page on the philosophical point of land ownership (can anyone be justified in claiming to own land?) and particularly in regard to 'traditional owners' elsewhere on this site.

In places it has been written that "the traditional

owners of the Flinders Ranges would prefer that visitors do not climb

Saint Mary Peak", the highest mountain in the southern half of the state of South Australia. I have not been able to find any more information on this 'preference' other than an unsubstantiated statement that "St Mary Peak is central to the Adnyamathanha creation story". I have read elsewhere that the Wilpena Pound Range is a part of the traditional owners' mythology, but not that the peak itself had any special significance.

I don't know anything about the motivation for this opposition, how it is justified, how many people were involved in deciding to oppose climbing, whether the decision was unanimous or contested, nor who exactly was involved in making the decision. If the 'preference' for people to not climb was seriously based surely information on these points should be available.

I can only think that whatever justification there is for the 'preference' was to avoid the offending of spirits.

Of course there is not the slightest evidence that these spirits, or for that matter any god or gods, exist. To believe in the supernatural is to suffer from delusions.

Religious beliefs have probably lead to greater crimes and denial of freedoms than anything else in human history (and probably well before human history too); consider the many crimes committed by the people of the Bible as a few examples.

It has been suggested that I should respect the beliefs of the 'traditional owners' and refrain from climbing Saint Mary Peak.

At the time of writing Muslim Palestinians and Israeli Jews were killing each other in Israel and Gaza while Catholics and Protestants were looking like going back to killing each other in Northern Ireland.

Even though they believe in the same imaginary God their differing myths seem to make it impossible for them to live together in peace.

The fundamentalist Muslim Taliban, who opposed women's rights, the arts and many freedoms were making advances in Afghanistan and a woman who had been accused of witchcraft had been tortured and killed in Papua New Guinea.

Catholic Christians have killed thousands of Protestant Christians (and vice-versa) in the past, Shiite Muslims kill Sunni Muslims (and vice-versa) periodically, Hindus kill Muslims (and vice-versa) in India and Buddhists burn the villages of Muslims in Burma; all over the beliefs that they hold in the complete lack of supporting evidence.

All these religious and superstitious (religion is a synonym for superstition) are delusional; it is as simple as that.

Australia's Prime Ministers Abbott and Morrison were public in their strongly held Christian beliefs (delusions) and they did their best to damage the world I love by trying to get as much fossil fuels burned as possible.

No, I have little respect for delusional beliefs.

My wife and I climbed Saint Mary's Peak one easter about 1976. We were either the first for the day to reach the top or close to it; on our way down we counted about 250 people on their way up. I believe that the view from the top is one of the most beautiful views I've ever seen. For a few people to deny many people the freedom to contemplate this view - on grounds of superstition - is, in my opinion, unsupportable, sad and an abuse of power.

Of course even hiking to the top of the Peak does have some impact, but if the alternative is going for a drive, or to do a sight-seeing flight, then that impact will be much greater. If we want to minimise our impact on the Flinders Ranges we should not visit them at all, but walking will always have much less impact than driving or flying.

Should the enjoyment of a great many people be curtailed because of the delusions of a few? I would say definitely not.

-

"The only part of the conduct of any one, for which [a citizen] is amenable to society, is that which concerns others. In the part which merely concerns himself, his independence is, of right, absolute. Over himself, over his own body and mind, the individual is sovereign."

- John Stuart Mill, in On Liberty

The freedom to die at a time and by a method of one's own choosing should be a fundamental human right. I have written on

euthanasia, assisted suicide and suicide and on

suicide as a rational decision elsewhere on these pages. The obtaining of that freedom will be a

milestone in the development of human society.

In Australia the laws on when, where and how drones can be flown are unnecessarily restrictive. I have written more about this on

another page on this site.

Recently (as of the time of writing, June 2005) we, in Australia, have heard

suggestions that our government should consider legalising torture under

special circumstances.

I believe that would be a great mistake, for the following reasons:

- It goes against two great moral rules:

- The victim may be innocent of the crime of which he is suspected;

- The victim's crime may not be a crime when looked at from a point of

view different to that of the torturer:

"one man's terrorist is another man's freedom fighter";

- Almost everyone would agree that the intentional inflicting of pain on any

animal is, in itself, bad. Torture is a wrong that can only be justified by

bringing about a greater good. But very often, when people do bad with the

aim of producing a greater good, the end that is actually achieved does not

justify

the means employed;

- It would be quite immoral to require an employee to use torture;

- If the government of a country uses torture, then the opponents of that

government will feel more justified in using cruel and immoral methods;

- It will cause fear and dread of government and authority by the citizens.

In a democracy the citizens should respect police forces, not fear or dread

them;

- Those who authorise the use of torture in 'special' cases will be tempted

to also authorise it in other cases;

- Those who do the torturing will have a hard time living with their

consciences; this will be a burden to them in later life. They will also be

despised by the general populace if what they have done becomes known;

- The torturers will become brutalised by their work;

Torture is also discussed under

Does the end justify the means?

| |

|

No one rule fits all cases

In philosophical ethics the aim of maximising favourable outcomes and minimising unfavourable outcomes is called utilitarianism.

There are cases when it can lead to injustices. For example if a large majority were to enslave a small minority it might be claimed that the total of the advantage to the majority would be greater than the disadvantage to the minority, but most people would not accept that justice was served.

|

|

Philosophers have filled books with attempts at answering this question. I will shortcut and simply suggest that in most cases good can be defined as that course which will lead to maximising favourable outcomes and minimising unfavourable outcomes.

Sometimes it will be necessary to do some harm in order to achieve a greater good. For example, most would agree that it is acceptable to tax the rich so that we can help the poor.

When deciding on 'the good' it has often been

thought sufficient to consider other people. With the

harm that has been done to our environment in the recent past

(for example damage to the ozone layer and the extinction of

species caused by greenhouse warming) it has

become clear that we must consider the whole of the part

of the earth that supports life, the biosphere.

There are simple actions that would almost universally be considered

good; for example, collecting rubbish from a roadside and disposing

of it

properly.

Other actions, generally of a more complex nature,

may be thought good in one age or in one society, and less good in

another. Clearing scrub to produce open farmland was strongly

encouraged in Australia in the nineteenth century with the result

of widespread soil salinisation and other problems in the twentieth century.

Introducing Old-World animals into Australia, to make Australia

more like Europe, was once thought good; it has caused huge and

irreparable harm to the Australian environment.

Confucius suggested that a gentleman (who he defined as

a man who lives a moral life rather than a man of noble birth)

would take as much trouble to discover what is right as lesser

men take to discover what will pay.

The Golden Rule,

'do to others what you would like them to do to you' is one way that

you can decide on whether an action is ethical or not.

Another is to consider

'what if everybody behaved that way?'

What if everybody behaved that way?

It may help to decide whether a particular behaviour is ethical by considering

what would result if everybody adopted it.

For example, if one person throws his rubbish out of his car window little harm is done, if everybody did it our roadsides would quickly become a mess.

| |

In a world that is grossly overpopulated it is irresponsible and unethical to have many children. Surely it must be obvious what would happen to world population "if everybody did that".

The per-capita greenhouse gas emissions for Australia is about 25 tonnes (CO2 equivalent) per year, so in a life time each person would be responsible for nearly 2000 tonnes.

I leave it to the individual to decide what is a responsible number of children, but I can't see any justification in having more than two.

|

|

In Australia some people drive big, heavy four-wheel-drives (4WDs, SUVs) because they know that anyone in a 2-tonne 4WD who collides with a 1-tonne compact car is likely to come out better off than the people in the little car.

What if everybody did that?

We'd all be driving around in tanks, no-one would be better off, and greenhouse gas emissions would go far higher.

This is a behaviour that has a short-term advantage to a few, but is to the long-term disadvantage of all; and is therefore unethical.

This ethical point is also known as

the tragedy of the commons, discussed

elsewhere on this page.

(No one rule is sufficient in all cases.)

This point

is especially appropriate in this age of greenhouse warming/climate

change. Consider your life-style and think what would happen to the world

if everybody behaved like you do. If you live the life of a high-consumption

Australian or USian,

think how much worse the climate change problem would be if everyone in the

world was responsible for producing as much carbon dioxide and for

consuming as much petroleum as you.

The Australian government has tried to excuse Australia's very high

production of greenhouse gasses on a number of occasions by

saying that the total greenhouse gas produced by Australia is a very

small percentage of the world's total. Australia produces about 1.5% of

the world's total annual greenhouse gasses, but Australia has only about

0.3% of the world's population. So, using the rule, 'what if everybody

behaved that way?', if every person in the world was

responsible for the same amount of greenhouse gas production as the average

Australian then the world's total would increase five fold – an absolute

disaster!

This ethical question is discussed in greater depth in my page on

greenhouse and Australia.

The greenhouse/climate change problem has come about because people have

not considered this moral question.

No-one has bothered about the amount of CO2 that they are responsible for

releasing because it is trivial in the big picture; but they don't go

on to think that they are one of six billion people and they have a moral

obligation to use no more than one six billionth of the earth's resources.

A number of Australians who work in the mining industry air-commute to

their work. For example they might fly a couple of thousand kilometres

from Perth to the NW of Western Australia every few weeks.

Consider the amount of plane fuel used and greenhouse gasses produced.

What if everybody did something similar?

Perhaps these people, as individuals, don't have a choice;

perhaps that is the only way they can get to and from that job; the

fact remains that it is unethical because they are producing more than

their share of CO2.

| |

|

This section added 2015/08/16

|

|

This bit was first written when I was trying to put my thoughts together

on what I could best do with my time.

Then I decided that I could modify it to perhaps be of some use to others.

Ask yourself:

- What can I do with my life that will serve the most useful

purpose to society as a whole and to the planet?

- What are the most important causes I can espouse?

- Where is the greatest opportunity?

- Where do I have some chance of having an impact?

A large factor is: what are your talents and resources?

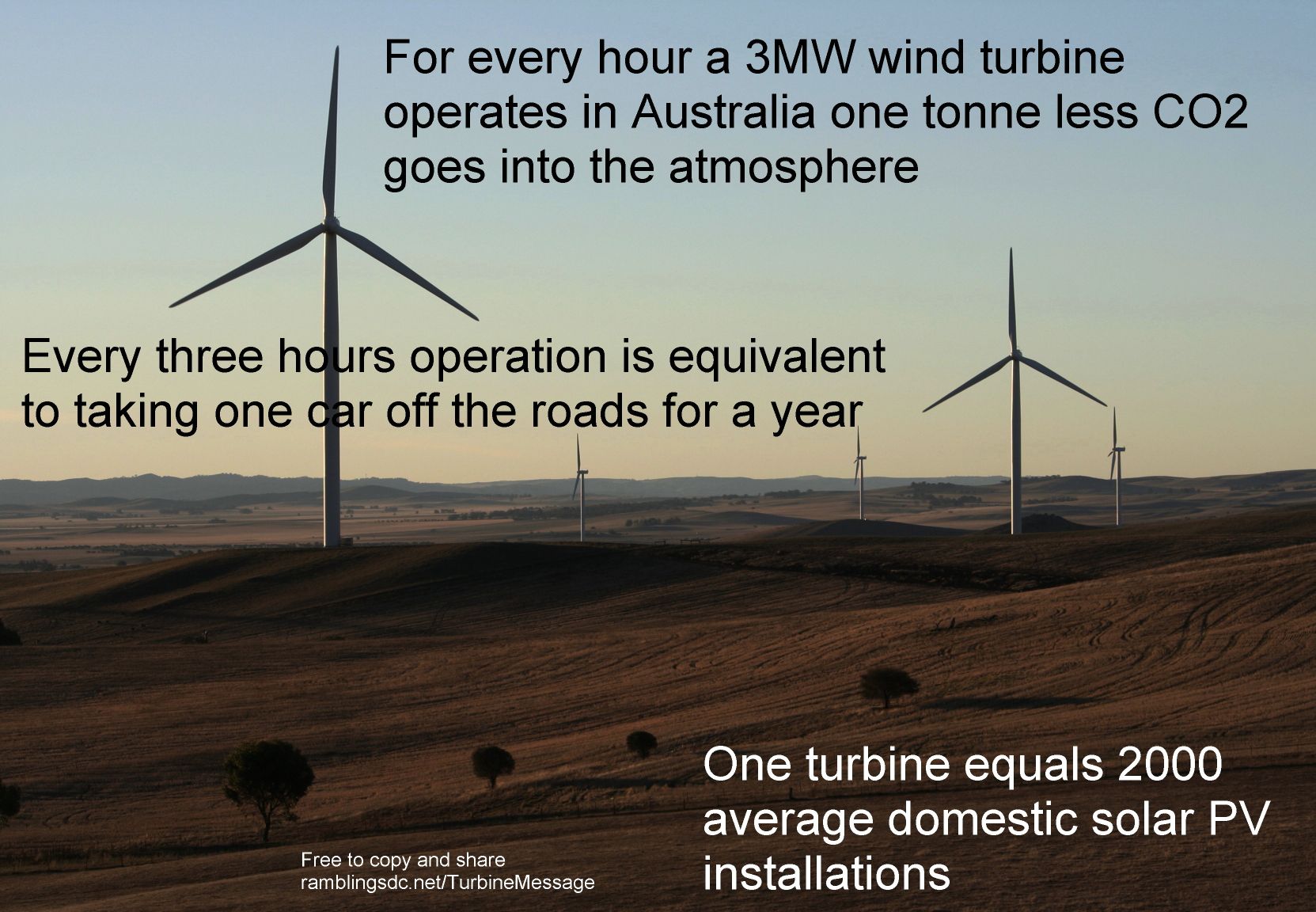

For myself (as an example) I decided that the best I could do, under the

circumstances, is to continue to try to dispel the myths about wind power

and contrast it to the proven harm done by the coal industry.

(Wind power can, to some extent, replace coal-fired electricity generation.)

There is a great unjustified mistrust of wind power in Australia and

insufficient recognition of how bad coal is.

From experience it seems that there is no point in trying to change the

minds of those who have an entrenched hatred of wind power, but I can work

on the many who are unconvinced one way or the other.

Others will decide that they can do the most good in entirely other directions.

Philosopher Peter Singer wrote a book titled 'The most good you can do'.

It leans toward a philanthropic approach: how you can achieve the most good

with the money that you can spare or whether you can do more good by getting

a highly paid job so that you can afford to give more.

Singer is well known for his advocacy of

animal rights and in particular the cruelty

involved in modern factory farming.

Singer's book is a good place to start, but I hope that you will also consider

some of the points made in this section.

Some people will come to the conclusion that they can do the most good by

getting involved in activism of one form or another especially if they have

little money to spare.

What other good can you do?

- Reduce your 'environmental footprint'

- If you buy or build a house, aim at a small, energy efficient one;

- Minimise the carbon emissions of your travel (walk, cycle, use public

transport, buy a smaller more fuel-efficient or electric car, or just

travel less);

- Eat less meat;

- Many more suggestions on another page;

- If you have investments, change away from those that are unethical;

- Get rid of investments in fossil fuel companies;

- Take your savings out of banks that make unethical loans (in Australia

for example, the big banks loan to fossil fuel companies and mining

companies that will greatly damage the Great Barrier Reef;

- Buy your electricity from responsible energy retailers, not those

(like Origin, Energy Australia and AGL) that lobby politicians against the

adoption of renewable energy;

- Use social media to tell your friends what you are doing;

- Spread awareness that the coal industry

has no future (financially as well as

environmentally;

I am a hopeless speaker; I can never think of the words I need as I need them,

so I avoid public speaking, talking to politicians, etc.

How I have tried to do good:

- Involvement in

walks: the first for a solar-thermal

power station, the second pressing the Australian government for serious

action on climate change;

- Involvement in

removing rubbish from roadsides and working in the

local wetlands;

- Many of the pages on this site are my efforts to do good;

Children should not only be taught facts and how to use processes to

achieve aims (such as arithmetic operations), but how to think effectively

and critically.

All children should be taught at least the basics of philosophy because

philosophy is all about freeing one's thoughts and understanding the

limitations of knowledge.

And, in the context of this page, all children should be taught the basics

of ethics: the philosophy of morality.

A period once a week for all students to study philosophy and ethics

would be well justified and productive as well.

Learning to think critically would make all learning more effective.

Failing a dedicated period for all students to study philosophy and ethics,

many schools have a weekly session during which the children can receive

religious instruction.

Those children who do not associate themselves with any particular religion,

or a religion for which no instructor is available, often are allowed to

use this period for revision or personal study.

This period could be used to study ethics, and the children could be given

the choice of whether to study religion or ethics.

Learning ethics (or philosophy or critical thinking) would be a much more

productive use of the childrens' time than learning religion.

Ideally teachers trained in ethics would be used, but if they are not

available then volunteers from the community might be able to be found.

| |

|

Who am I to lecture on ethics?

Is it hubris?

Do I consider myself an expert, or perhaps a good example of moral living?

No. Ethics is simply a subject that I enjoy giving some

thought to. On this page I am attempting to express some of the

conclusions that I have reached.

|

More ramblings on Ethics in government

Other pages on my site that deal with ethics and governments

are:

|

|

All of us can have an effect on our governments and we all have a

responsibility to try to improve our governments.

Those of us fortunate enough

to be citizens of democracies can easily and safely put forward

our opinions, those not so fortunate should still try to move

their governments toward moral courses.

"Every nation has the government it deserves", Joseph LeMaistre.

Citizens of democracies have, I believe, a responsibility to

keep a check on the actions of their governments.

While the urging of one citizen will have little effect, it will

have an effect.

Many citizens of democracies complain that the only say they

have in the government of their country is to vote at election

time. This is a pathetic excuse that lazy people use to justify

their apathy. If they were sincere in their stated desire to

modify the way their country is governed they could:

- Explain their concerns to their local member of parliament

and urge him/her to act upon them;

- Contact the relevant minister and urge him to act;

- Contact the leader of the government;

- Write to newspapers explaining their point;

- Join a political party and take an active part in the

democratic process;

- Run for parliament (congress, whatever) themselves;

- Produce an Internet site and place their concerns on it.

Governments have, it seems to me, always tended to think only

of the short-term. This is notoriously so with democratic

governments; they are always considering having to face the

voters at the next election. All citizens, if they want to be

good citizens, whether they are a part of a government or not,

should try to press their government toward giving proper

consideration to the long-term effects of their actions.

Governments, whether local, regional, federal or international

(the UN), tend to place too much emphasis on economical

matters while tending to neglect ethical matters. This is much

the same thing as thinking short-term rather than thinking

long-term. An immoral decision based on economical

considerations might have short-term benefits, but will probably

have long-term disadvantages.

Governments also tend to favour 'development' over conservation.

Perhaps it is easier to produce a visible outcome; if a new

industry is established in a town then the mayor can feel that

this is something that he has done for the town. If, on the

other hand, he was to protect remnant roadside vegetation, the

result would be less obvious, although, in the very long term,

perhaps more important. (Profits and income, though necessary,

are transient; biodiversity, once lost, will take millions of

years to recover.)

| |

All of the people all of the time

A society in which everybody behaved ethically all the time would function

wonderfully well; but that is unrealistic.

A society in which most people behave ethically most of the time functions

acceptably well; that is what we have in most respects.

A society in which most people behave unethically most of the time will fail;

that is what we have in regard to greenhouse/climate change, at least in

the western world.

Ethics and wind power

Ethics in relation to opposition to wind power and renewable energy in

general are touched on in my page

Wind Energy Opposition.

It particularly deals with exposing those who oppose the adoption of wind

power in Australia for unethical reasons.

|

|

"In Australia, we know that water for irrigation is limited, and we are

beginning to discuss how best to divide it up.

Here's one way of doing it: let those with the biggest pumps take as much

as they want, never mind what that leaves for others.

Not fair? But then, why are we using exactly this method of dividing up a

scarce resource right now – not with water, but with the atmosphere?

Perhaps because we're not used to thinking of the atmosphere as a scarce

resource, we don't see how unfairly we are behaving."

Philosopher Peter Singer writing in The Age, 3rd April 2008

Society's refusal to greatly and urgently reduce the rate of production

of greenhouse gasses is going

to condemn future generations to living on a badly damaged planet.

Compared to the rest of the world, especially the poorer nations, most Australians and people of the USA produce far more than their fair share of greenhouse carbon dioxide when the capacity of the world to handle this is overloaded.

How can politicians in Australia and the USA ignore any ethical responsibility to reduce our shockingly high per-capita emissions?

Any calculation of the amount of carbon dioxide that the world can sustainably

handle shows that, per person on earth, it is a small fraction of the amounts

produced by the people of Australia and the USA.

In most cases it would be easy for these people to reduce the amount of greenhouse gas that they produce; buy smaller cars, use public transport more and their private cars less, etc.

We should be replacing fossil fuels with

renewables.

Consuming more than your share when you know that all will suffer for your

consumption in the long run is certainly unethical. The great majority of

Australians and

USians must be aware of

the greenhouse/climate change problem.

I think the answer is that these people simple do not think of it

in these terms; they are just doing what those around them are doing, they

cannot see the trees for the forest. The citizens of Australia and the USA

need to be educated about greenhouse responsibilities, but their governments

have little or no interest in lowering greenhouse emissions so will not

invest anything significant in this education.

(One of the major political parties in Australia, the

Liberals are particularly

lacking in ethical standards on this point.)

The 'Tragedy of the Commons' refers to an ethical dilemma where the

short-sighted selfishness of a few people can cause environmental

destruction in spite of the good intentions and best endeavours of everyone

else.

The term originates from the Commons, or common land, of Britain.

Britain had land reserved for the use of all.

Individuals could run a few stock on the commons or plant a small garden

and grow some vegetables or fruit trees.

The 'Tragedy' comes from the fact that, so long as everyone considered

the needs of their neighbours and remembered that each had a responsibility

to protect the commons as well as a right to use the commons all was well,

but the good of all could be damaged by the greed of a few.

If 90% of those who used the commons did so carefully and responsibly,

the remaining 10% could still overstock the land and damage it.

If the 90% reduced the numbers of their stock when they saw that overstocking

was a problem, the 10% could increase the numbers of their stock, increase

their profits and increase the damage done to the land.

This problem is covered by the question

What if everybody behaved that way?, discussed elsewhere on this

page.

This is exactly what we see with

greenhouse/climate change.

Instead of some people in a local community sharing some common land there

is the global community sharing the atmosphere.

When there were fewer people on the Earth and we all produced only a little

greenhouse gas all was well, but when our numbers multiplied and some of

us started producing far more greenhouse gasses than others climates

started to change.

But then people realised that if some tried to live within the limits of

the capacities of the Earth's natural systems, but a few did not, the

tragedy would continue.

The wealthy nations have done most of the damage.

They have caused most of the gasses to be released into the atmosphere

to cause the level of climate change that we are seeing in the early

twenty-first century.

What we need is for an agreement between most nations (we cannot wait for

an agreement between all nations) to somehow share the Earth's natural

systems without excessive damage.

Those nations that will not agree voluntarily will have to be induced

to conform by pressure from the others.

Should one try to maintain the highest standard of ethics when one sees much lower standards in others? Or should one be content to just maintain a little higher standard than that observed in others in one's society?

I'll give an example. It is wrong to damage the environment more than one needs to; as mentioned above, it is impossible to live without doing some harm.

The burning of fossil fuels is widely recognised as the main cause of

climate change,

ocean acidification,

sea level rise and

ocean warming.

The air pollution from the burning of fossil fuels

kills millions of people world wide each year.

It follows, therefore, that we should, as individuals, try to minimise the greenhouse gasses that we are responsible for. Most of Australia's electricity (most of the world's electricity?) is generated by burning coal – one of the main causes of greenhouse gas production. If we want to minimise our own contributions what

should we do?

- Be aware of how much electricity we are using and always try to minimise it?

- Not use any electricity from the grid? Generate our own by using solar panels;

- Pay a little extra and buy '

green' electricity;

How much trouble should one go to in order to minimise one's

electrical consumption? Many other people don't care at all,

so should one be content to do a little better than the

majority?

If one buys green electricity, should one go to the expense

of buying 100% green electricity, when most other people

don't buy any? Would buying 25% green

electricity be enough?

I'd suggest that one does what one reasonably can; what one

can afford to; that one maintains the highest standard of

morals that one can reasonably achieve.

That other people have low ethical standards should not

effect one's own ethical standards. Bad behaviour in others

does not excuse bad behaviour in oneself. On the other hand

to live shivering in the cold rather than switching on a heater,

because one believes it unethical to consume electricity and so

add to the greenhouse problem, I would suggest is excessive.

(I think Buddha said something to the effect of moderation in

all things, walk the middle path?)

Plato held, in The Republic, that to be moral is in one's own interest, that even from a selfish perspective morality is the best course.

| |

This section added

2023/12/30

|

|

I have believed for many years that we should always consider the consequences of whatever we do. Humans are intelligent animals, although we do have to make an effort to use that intelligence. It seems that many have got into the habit of just drifting through life as far as the consequences of our actions are concerned. Some of us, apparently many of us, don't care what fall out there is from what we do.

It is a great pity for those who do care, that so many don't. We all have to suffer jointly many of the consequences of people's actions as individuals. In particular, the future of all life on Earth is impacted by the emissions that each and every one of us is responsible for individually.

We have choices in what we do all the time. For the sake of our shared world we should all consider how we make those choices, not just selfishly, but at least with a thought to altruism.

| |

| |

Six big and heavy 4-wheel-drives and one small fuel-efficient car in the

Flinders Ranges of South Australia.

Are the gas-guzzlers needed?

Our little car (the Jazz on the left) weighs about half as much and handles the dirt roads with ease and it is quite capable of towing a tent trailer or small camper.

| |

Many people would consider ownership of a car of their choice a

right, but is it? Our cars are one of the greatest producers of

greenhouse gasses. If every person in the

third world owned a car and ran it as much as we in the West

run our cars then global warming would quickly be increased to

intolerable levels.

So, if running a car is something that is unsustainable if

everyone in the world were to do it, can we justify our cars?

I suspect not.

Of course the size of the vehicle and its fuel consumption is

also an important factor. A large four-wheel-drive (4WD, SUV) car could

easily consume twice the fuel of a small car.

(USians call 4WDs SUVs –

sports utility vehicles – sometimes BinLadenmobiles.)

I use a car. I can't see any reasonable alterative. But I

try to minimise my car use, and try to avoid running a car

that is bigger than I need. It's important to think about your

consumption and your contribution to global pollution; if you

think about it perhaps you will become a part of the solution

rather than being just another part of the problem.

An interesting page with an American

point of view on SUVs is at

Santa Clara University.

The graph below indicates that if we can share the use of small cars

rather than using a big 4WD on our own we might reduce our greenhouse

impact about nine fold. It also shows that sharing our vehicles,

whether big 4WDs or minis, can greatly improve their sustainability,

and therefore their ethical justifiability.

(In the graph I have, for simplicity, considered the driver to be a

passenger.)

Kg CO2 per passenger Km for various vehicles and

numbers of passengers

|

This graph shows how the amount of CO2 released from a car,

when figured on a per passenger basis, varies

depending on the size of the vehicle and the number of passengers.

The tall purple bar in the back row indicates that in a big 4WD (SUV) with

only one passenger about 0.4kg (400 grams) of CO2 is released

every kilometre travelled.

The short blue bar in the front row shows that at the other end of the

scale, in a mini car with four passengers, only 0.045kg (45 grams) of

CO2 is released every passenger-kilometre travelled.

|

| |

|

This section added 2016/09/11

|

|

We all have an ethical obligation to try to minimise our environmental

impact on the Earth.

One of our greatest impacts is the greenhouse gasses that we are responsible

for releasing into the atmosphere.

| |

|

The ultimate

Of course the ideal car would not emit any greenhouse gasses.

An electric car using electricity generated renewably is such a vehicle.

|

|

As of September 2016 my wife and I had driven a Honda Jazz for about 11 years.

Its average fuel consumption was about 5.6 litres per hundred kilometres.

I thought it would be interesting to make some calculations on the total

amount of fuel it had consumed, total CO2 emitted, and compare this

with more common and higher consumption cars.

As of September 2016 our Jazz had travelled 170,000 kilometres; the

calculations below are based on that and a fuel price of Aust$1.20/Litre.

| Car | Fuel consumption

L/100km | Fuel consumed

Litres | Cost | Cost difference

| CO2 emitted

Tonnes | Emission difference

Tonnes

|

|---|

| Jazz | 5.6 | 9,520 | $11,424 | | 23.8 |

|

|---|

| Medium car | 8.0 | 13,600 | $16,320 | $4,896 | 34.0 | 10.2

|

|---|

| Large car | 10.0 | 17,000 | $20,400 | $8,976 | 42.5 | 18.7

|

|---|

| Gas guzzler | 14.0 | 23,800 | $28,560 | $17,136 | 59.5 | 35.7

|

|---|

The cost difference column shows how much more a larger car would have cost

us for fuel than the Jazz.

(This does not consider the higher capital cost of a larger vehicle, lost

income from money invested, and higher maintenance costs of larger vehicles.

On top of that a larger car would have required more garage space.)

The Emissions difference column show how much more carbon dioxide would have

been emitted had we run larger cars instead of our Jazz.

Another important factor is the convenience of easier parking for a smaller

car.

Some people are more wealthy than others. Those who are wealthy may have

worked hard to produce that wealth in the past; some may have been given

their wealth by their parents. Most people who live in Western countries

are wealthy compared to most residents of the Third World.

| |

Criminal use of wealth

| |

This section added

2021/05/17

|

|

The wealthiest person in Australia, Gina Rinehart, uses some of her great wealth, much of which has come from mining of coal, to try to convince people that climate change is not happening or has nothing to do with human activities.

She could do great good (for example she could give $5,000 to each of the million poorest Australians and still be the most wealthy person in Australia), but instead she choses to do harm to our shared planet.

She is just one of a great many wealthy and/or powerful people who misuse their wealth; Rupert Murdoch and Clive Palmer are conspicuous others.

|

|

Wealth brings with it advantages. Wealthy people have options, the very poor

often have few choices on how they can live their lives. Wealth brings with

it power, poverty equals powerlessness.

Consider my life today compared with an African peasant farmer; for the sake

of the exercise think of the two of us as if we had no past. I, who am

retired and financially comfortable, get out of bed and write a bit on my

computer before having breakfast and going out to water some trees that I have

planted along some roadsides. All things that I have chosen to do.

The

African peasant probably gets out of bed and is straight into work that must

be done, work that he/she has no choices in. His breakfast is much more

frugal than mine, his health is more precarious, he could not afford to buy a

computer even if he wanted one, he probably can not be at all confident that

he will be able to feed himself, or his family, in the year to come.

Why should I be so well off and the African not? Is this situation just?

I suggest that those of us who are wealthy have a responsibility to share with

those who are poor. If you have a much larger house than you need, if you

have more bathrooms than you can use, if you regularly have holidays on

luxury liners or in five star hotels, look to your ethics.

Animals have even less power than African peasants. Those of us who have

options certainly have responsibilities to animals.

I am retired now (now being March 2004), have been for six months. That

means that I am living off my superannuation and investments.

I am consuming products that are produced by other people,

while not, myself, producing much.

I'm still physically reasonably fit, but at the age of 58 I believe I'd have a hard time finding paid employment if I tried.

Is consuming the products of other people's labour, while producing little oneself, ethical? I suspect that Carl Marx would have had something to say about it.

(In the 17 subsequent years I have done voluntary work and other things so as to continue to contribute to society and the world.)

| |

|

Photo thanks to

News.com.au

Seventeen thousand visitors left the supposedly revered Anzac Cove site

strewn with rubbish after the 90th anniversary dawn service on

Anzac Day 2005.

|

|

From the point of view of ethics

It has become a tradition of Anzac Day – Australia's commemoration of

what is held to be a major historical marker in the making of the Australian

nation – for a large number of Australian and New Zealanders to gather

at Anzac Cove on Gallipoli for the dawn service.

The photo on the right shows how much rubbish the visitors leave behind them.

Dumping your rubbish for someone else to pick up is not the most unethical

act you can do, but it is unethical, and I suspect it demonstrates an

unethical mind-set.

It is a question of self versus society. The person who dumps his rubbish on

the ground is showing that he/she believes that his convenience, in getting

rid of his rubbish quickly and easily, is more important than the consequences of his actions on others. He apparently believes that he is more important than the place he is damaging or that he is more important than those who must come later and clean up.

This same concept is shown by Australian Coalition governments by their insistence on the right to dump carbon dioxide into the atmosphere to the detriment of the whole world.

In the Anzac Cove case, this is harder to understand since one would think

that the place would have to have some 'spiritual' significance for these

people who go to the trouble of visiting it. Yet they have no hesitation in

rubbishing it? Do they just not think about the contradiction?

I have used the collection and proper disposal of roadside

rubbish as an example of an act that almost everyone would

agree was ethical. However, when one tries to define

'proper disposal' one finds that the task is not so simple.

- Let the local council take it to their landfill? Is

landfill an ethical way of disposal of rubbish?

- Is the question of what the local council does to

the rubbish your ethical problem?

- Separate the organics and compost them yourself?

Recycle what you can.

What to do with the remainder?

- If you don't have the space to compost the organics,

should you burn them? What of the smoke?

Perhaps you do the best you can in the time you have and with the facilities that are available to you.

| |

|

I can't resist including one of my favourite quotes here:

"Good people will do good things, and bad people will do bad things.

But for good people to do bad things – that takes religion."

Steven Weinberg, Nobel laureate

|

|

Are there some people who are entirely good and others who are entirely bad?

It seems unlikely.

There are certainly some whose bad deeds have come to dominate our impression

of them as they are recorded in history; for example Adolf Hitler.

There are others whose historical image has changed over time.

Moa Tsi Tung, for example, used to be thought of as something of a benign

father figure of China during the period of its modernising, but over the

past few decades, as more records of his actions come to light, he seems

to have been exposed as a selfish and unfeeling dictator who did much more

harm to China and the Chinese people than any good he did.

In the case of my country, Australia, the period from 1996 to 2007 was

dominated by the policies of Prime Minister John Howard.

He presumably was motivated by a desire to 'improve' Australia, but he

aligned it with the USA in that country's

wars of global

domination and he was George W. Bush's greatest ally in slowing the

world's response to the massive

climate change problem.

He dominated the parliamentary Liberal Party to the point where very few

other members seemed to have found the will or courage to speak out

against him.

Yet while his Prime Ministership was largely negative for Australia,

and certainly for the world, I think

it might be simplistic to just say that he was a 'bad' man.

'White collar' criminals such as embezzlers seem to have traditionally

been thought less 'bad' than violent criminals, although one wonders which

have caused the most harm.

Surely the seriousness of a crime, or unethical act, should be measured

by the amount of harm done.

Then shouldn't we measure the harm done by greedy

corporate bosses according to the amount

of financial harm that their rapaciousness does to other people?

For example, a public company chief executive officer who takes two million

dollars a year more than he needs from the profits of that public company

can be thought of as taking a thousand dollars a year from each of a thousand

employees of that company and a thousand dollars a year from each of a thousand

small investors in that company.

This surely causes unnecessary hardship to a great many people; unnecessary

because research has shown that increasing income, beyond the minimum level

required to sustain a comfortable lifestyle, produce very little, if any,

increased happiness.

The greed of the corporate CEO, while doing harm to many, hardly improves

the lot of the CEO himself!

Considered this way, are avaricious corporate CEOs among the worst, most

unethical, people in the modern world?

| |

|

This paragraph added 2017/03/26

|

|

On the subject of the worst criminals I need to mention a point I have

put forward on

another page: that dishonestly supporting

the retention of the fossil fuel industry and opposing the introduction of

renewable energy has to be the greatest crime in the history of humanity.

It then follows that those in positions of power who commit this crime would

have to be the greatest criminals in the history of humanity.

In early 2017 there two who are prominent in this group are Australian Prime

Minister

Malcolm Turnbull and US President

Donald Trump.

When I was in my twenties I felt concern that a number of people had done more

for me than I was able to do for them. I had been given accommodation by some

and was not in a position to do anything in return. I had been given help

with broken-down or bogged vehicles and could not return the favour.

I suspect that young people in particular tend to have more done for them

than they are able to do in return.

As I got older I developed the idea that while I could not return the favour

to the individuals who helped me – in many cases I had lost track of

them – I could help other people and at least 'balance my ledger' in

that I would do good for at least as many people as had done good to me.

I do not recall ever discussing this principle with anyone until a visit to

some long-time friends in England in 2004. They took my family and me to an

expensive dinner and refused to allow me to pay any part of the cost. When

they realised that I did not feel comfortable that they had paid the whole

cost of the restaurant meal, they explained that they had many favours done for

them in the past and they felt that by doing favours to us they were moving a

step toward balancing their 'good deed ledger'.

This principle can be taken a step further. We all have had a great deal of

pleasure from the environment; think of all the beautiful days that you have

enjoyed in wonderful places, the scent of flowers, the enjoyment of lovely

views, experiences with wild animals, and so on. We are indebted to our

environment. We can go some way toward balancing this ledger too, if we do

favours for the environment: plant trees where there are not enough trees,

control weeds, work to improve a

local park,

clean up rubbish, help to increase biodiversity,

or we can get involved in any of a number of campaigns to

slow climate change, stop

coal mining, etcetera.

Everyone feels anger sometimes when another person does something cruel or

morally wrong to them. I can well believe that many people feel,

probably rightly, that they have had a bad deal out of life; they therefore

become angry with society.

There are two things that we must be careful of here. First, it is certainly

wrong to punish some people for wrongs done by others, whether or not those

others happen to belong to the same group as those who did wrong.

Second, our anger can harm ourselves.

Anger and hatred do at least as much harm to the person who feels them as

they do to the person to whom they are directed. It is impossible to be

happy at the same time as being angry and hating. We all want to be happy.

I believe that it is a valid aim in life to be happy, so long as that

happiness is based on a solid foundation. One cannot meaningfully be

happy, for example, by taking drugs. Certainly one will never become happy

by collecting material possessions. We may feel some satisfaction if we

obtain revenge, but it is not the way to happiness.

So, do we allow people to do bad things to us and 'get away with it'?

No, I do not advocate that, sometimes we should seek justice; but we must not

allow our own anger and hatred to harm us. Overcome them, be happy!

Consider too, that the person who has harmed you may well learn in later

life that he has done wrong and, in so doing, has harmed himself;

what sort of long term happiness can anyone obtain by harming others?

People change. Many go through periods in their lives when they behave

badly; most eventually move out of that error. If possible, we should

help them see that it is an error rather than become angry or hate them.

Easy to say, hard to do!

| |

Philosophers have argued about the problem of knowledge for centuries.

As in so many things, the philosophers have not come to a single, agreed

conclusion.

I suggest dropping the concept of knowledge in the philosophical sense.

Knowledge can never be certain; there must always be doubt.

In fact, perhaps the acceptance that absolute knowledge is impossible is the

essence of science?

|

|

|

|

|

I believe that it is of fundamental importance that if we want to have any confidence in our beliefs we should continually examine them and make sure, as far as we can, that they accord with the available evidence.

| |

Descartes with his "I think, therefore I am" showed how very little we can be

sure of.

Great harm has been done by those who believed that they knew the truth;

consider the wars of religion and the

slaughter of 'heretics'

over the ages.

I don't remember who the writer was, but I remember reading an excellent analogy. For every theory that may be true or may be false (as an example think of organic evolution) imagine a horizontal wire attached to a wall. On the wire there is a bead representing evolution.

At each end of the wire is a cup.

If the bead is pushed along the wire until it falls into the left cup this indicates that you totally disbelieve that organic evolution happens. If the bead is in the right cup then it indicates that you have absolutely no doubt that organic evolution is a fact.

We must all endeavour to keep all our beads on the wires and not in the cups.

We must never believe that we 'know' what is right and what is wrong,

what is true and what is false. We certainly should pursue this knowledge, but we should always retain a sufficiently open mind to admit that we could be wrong.

One of the greatest of the many evils that have come from

religion is the unquestioning

belief in being correct while others are in error.

Why should a national flag be 'sacred'? Why should the symbol of a nation,

the nation itself, or its government, be above criticism?

Looking at the balance of good and bad; some people will be offended if

they see their national flag burned, but perhaps more good will be achieved

by encouraging them to think about whether their nationalism can really be

justified. My page on

Patriotism discusses similar concepts. Patriotism is very close to

nationalism. We should be thinking of the Earth, rather than an

individual nation, as our home; nationalism/patriotism was probably never a

good idea.

Nationalism implies either "The government of my country is always right in

its dealings with other nations" or "I will always support my country,

whether it is right or wrong". The first assertion is plainly factually wrong,

the second is morally wrong; both are dangerous.

Some people claim that Australians (or whatever your national group is) fought

in the First and Second World Wars (or whatever your great conflicts were) for

the flag. Surely they did not. Surely they fought for principals such as

freedom from tyranny and the right to pursue happiness in their own ways.

I would hope they did anyway.

Governments have an interest in the patriotism or nationalism of citizens.

They can use it to obtain the support of their citizens against some real or

imagined outside threat (as the US and Australian government have done very

effectively in the fake 'war against terror'). I see no ethical argument in

favour of nationalism or the sanctity of a national flag.

"Of course the people don't want war. But after all, it's the leaders of the country who determine the policy, and it's always a simple matter to drag the people along whether it's a democracy, a fascist dictatorship, or a parliament, or a communist dictatorship. Voice or no voice, the people can always be brought to the bidding of the leaders. That is easy.

All you have to do is tell them they are being attacked, and denounce the pacifists for lack of patriotism, and exposing the country to greater danger."

Herman Goering, Nazi Reichsmarshall and commander of the Luftwaffe, speaking at the Nuremberg trials.

|

My page on killing and war is relevant here.

According to an annual UCLA [University of California, Los Angeles] survey

of college freshmen [first year students], "being very well off financially"

was "very important or essential" to 44 percent of students in 1965,

but that number has steadily increased, reaching 75 percent of students

in 2000.

It's curious to note that while prosperity has significantly increased

during the past fifty years, self-reported levels of happiness have stayed

the same.

The data are dramatic.

For example, while inflation-adjusted personal income has almost tripled

since 1956, the percentage of Americans reporting that they are "very

happy" has remained steady at 30 percent during the past 45 years.

Extract from 'Do The Right Thing', by Thomas G. Plante

I have written on another page about "How much income is enough?" and "More money does not necessarily lead to more happiness."

| |

|

Going-it alone?

If the Australian government did make an honest attempt to reduce greenhouse

pollution it would not be 'going-it alone' at all.

It would be joining a long list of countries, mostly European, that have

been seriously trying to become more ethical and more sustainable.

|

|

The argument has often been made that there is no point in Australia 'going-it alone' and reducing its greenhouse gas pollution because Australia is 'too small to make a difference'.

The fact that per-capita Australia's contribution to global greenhouse gas production is five time the average is either unknown, or more likely, ignored by those who use this argument.

I have dealt with this argument in greater depth in The great fallacy.

As it relates to ethics, it shows shallow thinking.

Everyone on earth has a responsibility to use no more than a fair share

of the planet's resources, including its capacity to take care of wastes.

The 'too small to make a difference' argument, as it relates to Australia

and greenhouse gasses, is shown to be false if one considers the

'What if everybody behaved that way?' test.

| |

This section added

2010/04/26

|

|

Since the fall of communism the world has been left with capitalism effectively running the economies of most countries and even of the world as a whole.

Problems with capitalism as it has been practised up to 2010;

- Capitalism is short sighted, it is a slave to profit and cares nothing for the environment and sustainability;

- Company directors are bound by law to place the financial welfare of shareholders above most other considerations – this has lead to many large corporations resisting action on climate change. (See also Corporate greed);

- Wealth gives some individuals an advantage over others that is ethically unjustifiable;

- Capitalism has lead to a very uneven distribution of wealth –

Western governments have failed to curb this increasing problem;

- The inheritance of wealth gives an advantage to people who have done

nothing to earn that advantage;

- The financial collapse of 2008 was due to a fundamental failure of the

capitalist system;

Update, late 2023

In 2023 capitalism continues to dominate the way that the world is run by humanity with consequent great cost to our shared environment. The money in the fossil fuel industries is so great that they continue to thrive despite the obvious need to urgently reduce emissions.

In our present

golden age, when there is perhaps more equality, democracy, freedom of thought, belief, speech and action than in any other time in history, perhaps the greatest departure from equality is an uneven and unfair distribution of wealth (property under another name).

| |

Wealth replaces class and cast

In the twenty-first century wealth has replaced the old class system in Europe and the cast system in India (and similar systems elsewhere).

In the old class system your power and position in society depended on an accident of birth. Similarly in the Indian cast system, if you were born in a high cast family you had advantages that were neither earned nor justified.

|

|

|

|

|

Very uneven distribution of wealth in 2023

According to Global Citizen Facts:

- The richest 1% own almost half of the world’s wealth, while the poorest half of the world own just 0.75%;

- 81 billionaires have more wealth than 50% of the world combined;

- The richest 1% own almost two-thirds of all the world’s new wealth.

And a billionaire emits a million times more carbon than the average person.

(See also conspicuous consumption on another page on this site.)

|

|

Those who have wealth have more power than those who don't.

Those who have the good fortune to be born into a wealthy family will most likely grow up to have much more power and privilege than those who are born into poor families.

The obscenely wealthy, including the

corporate bosses, have far more power over politicians in democratic nations than do the common people.

(Yet the fundamental principle on which their lives is based, greed, is unethical.

At the opposite end of the spectrum to the greedy corporate bosses are the numerous common people who freely volunteer much of their time for the public good – and they have little political power. Also see my page on

Contribution.)

There is an entrenched and generally overlooked injustice here that is as great as any in the modern world.

Was it ever thus?

I suppose even in the first civilisations there was a recognition of private property; and the more of it that an individual owned, the greater his status and power over his neighbours.

Hunter-gatherers, because of their life-style, would not have been able to 'own' much property, but even if they had better spears and axes than the others in their group they would have some advantage.

I am retired and I own my own house.

For that reason alone I am financially better off than most of those of my countrymen (Australians) who are retired but do not own their own houses.

At the most fundamental level, what does 'own my own house' mean?

The house and I are not joined together in any way that is physically different to the relationship the retiree who rents has with his home.

The other fellow has to pay someone else – a person who has no physical

connection to the house – for the privilege of using the house.

Ownership is a convention that goes back into prehistory and that we all accept without much thought.

How ethically justified is it?

(See also my page on Land ownership.)

Thieves try to redistribute property.

Probably in most cases, thieves remove property from the better off and

redistribute it to people who are less financially well off: that is, to

themselves.

(Although very often thieves steel from their neighbours, who are probably

little better off than themselves.)

Many of us would think that a redistribution of wealth from those who have the most to those who have the least could be ethically justified; but not many would approve of thieves who take the process into their own hands.

(See also my page on Theft.)

If wealth gives people power and advantage and those who are born into

families or countries that are wealthy have an unfair advantage compared

to others, is this situation acceptable in a world that supposedly values

equal rights for all?

Communist regimes have tried separating people from some of their property; making all the means of production the property of the State, and attempting to make everyone equal and an employee of the State.

It didn't work, at least partly because if people are to work their hardest they seem to have to have some advantage to themselves to aim for.

(Communism also failed because those who gained power were either corrupt or became corrupted by that power and their aim became holding onto power first and foremost.)

We have evolved to look after ourselves first, and consider the needs of others second; and those others whose needs we are most likely to give most consideration to will be our families and probably then our friends and associates.

Most would feel that the man who builds his own house has earned the right

to live in that house.

Similarly, the man who works at one job to earn money to pay someone

else to build him a house has a right to ownership and residence in that house;

so long as there is some equality between the two.

But does a man (a corporate boss, for example), who is payed twenty times

as much per hour as the builder, have the same right to ownership over

the house that is produced?

Does the man who inherited his wealth from his parents have as much right

to the house that he purchases with that money?

Wealth seams to be justified if it has been fairly earned, but those who

have got their wealth with disproportionally little effort compared to

others have much less ethical right to their wealth.

| |

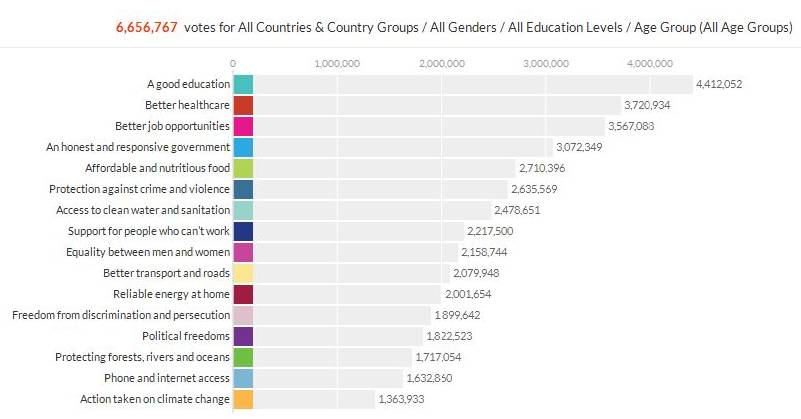

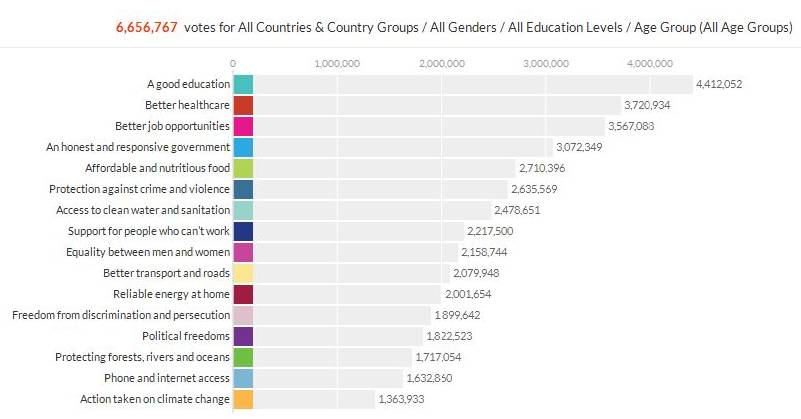

| "My World 2015: My Analytics"

|

|---|

| | United Nations global survey for citizens

| |

The graph on the right was copied from

My World 2015, by the UN.

It shows a number of people's concerns ranked in order of priority.

From an ethical point of view it is interesting to note that 'Action on

climate change', the most important of all the points for

coming generations and the future of the planet, is ranked last.

Those concerns that have the highest ranking have the more immediate and

personal impact.

When people judge the importance of concerns such as these, their priorities

are based not on the 'big picture' so much as on:

- How will it impact them personally?

In particular: will it affect them financially?

- How immediate is any effect likely to be?

- Is it close to home, regional, national or global?

Mazlow's hierarchy of needs is relevant here.

| |

This section written 2015/04/26

Edited 2017/04/23

|

|

Fighting in modern society is normally considered unacceptable.

Killing our fellows is certainly unacceptable and also illegal; many would consider murder to be the worst crime of all.

Except in war.

In war fighting and killing can not only become acceptable but even admirable – simply because they are sanctioned by the state.

We are expected to accept that killing the enemies of the state is OK; it is the brave and right thing to do.

What an absurd, ridiculous and contradictory situation!

In everyday life we are often highly critical of our governments.

We don't generally trust our governments, and considering the level of corruption we Australians are seeing in the Abbott and Morrison governments, the way they are pandering to the fossil fuel lobby and ignoring the need to act for the good of all people and of the planet, we would have to be stupid to trust them.

Yet if our government decides that our country needs to go to war against

some other country we become willing to fight, to try to kill 'the enemy' and die if necessary – because our government has somehow convinced us that right is on our side and killing has become the 'right thing to do'.

I've written more on this subject on another page.

| |

|

This section added 2020/10/23

|

|

There has always been a disconnect between ethics and the law; those who make the laws do not necessarily want to be bound by ethical considerations.

Laws are made by those in power in nations. Almost invariably the main aim of those in power is to hold onto that power.

At the time of writing (October 2020) perhaps the greatest disconnect between ethics and the law is in regard to climate change. Governments around the world support, and are supported by, powerful lobby groups such as the fossil fuel industries; this applies particularly in my country, Australia, which is one of the biggest exporters of coal in the world.

Ethical imperatives dictate quite unambiguously that urgent action on climate change should take precedence over most other matters, yet governments, particularly Australian governments, are resisting this.

Supporting the fossil fuel industries against reason and against the speedy development of renewable energy that we must adopt if our grandchildren and our planet are to have a future not greatly inferior to the present should be against the law, but is not.

As I have written elsewhere, for a person in a position of power to dishonestly support the fossil fuel industries and oppose action to reduce greenhouse emissions is the greatest crime in the history of mankind, yet criminals like the US's President

Donald Trump, Australia's Prime Ministers

Tony Abbott and

Scott Morrison are not being held to account at all.

| |

|

This section added 2023/07/14

|

|

A few days ago I visited the local pizza shop, one of the Domino's chain. My wife and I had decided to get a couple of pizzas for dinner for a change.

I noticed several 'deals' that were advertised, one of which was for two large pizzas, garlic bread and a 1.25 litre bottle of soft drink for $25. We certainly didn't want the bottle of soft drink.

I asked for two large pizzas. The girl said that would be (I think it was) $32. I pointed out that the advertised 'deal' was only $25. She said something like, 'Oh, you'd like the deal then?' I said 'yes please, but we don't want the drink'. She said 'you have to take the drink, it's part of the deal.' We did take 'the deal' together with the drink, and tipped the drink down the drain when we got home.

This form of marketing is an encouragement for people to drink sugary drinks that they don't need and don't necessarily want in a world in which sugary drinks are one of the main causes of the obesity epidemic. I'm sure it's not just Domino's that indulge in this very unethical practice, 'deals with a (sugary) drink included' are common.

| |

|

This section added 2017/03/27

|

|

Ethicists have worked for millenia to produce rules that can guide us in making

the correct decision in any situation, but it seems to me that there are no

rules that should ever be taken as absolutes, although several are

very valuable.

There are always exceptions to rules in ethics.

However, there are a few relevant philosophical rules to which I can think of

no exceptions:

- Never entirely accept the truth of anything without evidence;

- Always hold on to doubt;

- No person, group or creed holds all the answers.

While these rules can help us to wisely live our lives, they are not

helpful in answering ethical questions about right and wrong.

| |

|

If there are no hard and fast rules to ethics, why study the subject?

Why read what others have written?

We need to read what others have written in order to understand the many ways of looking at ethical questions; to enable us to put aside our own selfish point of view and see situations from the point of view of others, including philosophers over the ages, but also of other people in general and other sentient beings living now and yet to be born.

|

|

|

|

|

|

Are the moral rules given us by religions clearer and more useful than

those we might arrive at from ethics?

The short answer: no.

Religious texts contain many contradictions; consider the rules and laws

in the Old Testament of Christianity and how they changed with the New

Testament.

Even those who follow religion have to have some way to decide which rules

from scriptures should be followed and which should be ignored.

|

|

The rules that ethicists have developed can give guidance, but we must always

consider, "If I follow this rule in this case, is the result just?"

What this leads to, of course, is that there are no absolutes in ethics; there

is no prescriptive ethical right or wrong.

We could ask, "What use, then, is ethics?"

Its use is to help us see clearly, to view a situation from several angles,

to broaden our outlook, to see things from the point of view of others,

especially those others who have less power and 'rights', such as non-human

animals.

If there are no hard and fast rules, how can we know justice when we see it?

Intuition?

Surely not, intuition is terribly fallible!

In truth, intuition will play a part, but we must try to minimise it.

Perhaps if we study ethics we can train our intuition?

Surely right behaviour is important enough to justify some study.

In a practical case we can refer the situation and posible resolutions or

actions to the rules that ethicists have given us, and those that we have

worked out for ourselves, and see if they fit.

"Would that action accord to rule A?, rule B?, rule C?"

If it fails to fit several such tests it is more likely wrong than right.

If there seem to be several answers that are nearly equally likely to be

acceptable, we must give the point very careful consideration from several

angles.

What rules or guidelines, while not being absolutes, are valuable in helping

us find the correct answer?

- Utilitarianism (roughly, what would produce the best outcome for the

greatest number of people?);

- The Golden Rule;

- Ask "What would happen if everyone did that?";

- Ask "Will that make the world a better place?";

- Individual rights should be maximised so long as the rights of others are not infringed;

- A person should have absolute right over his or her own body;

- One has a responsibility to consider the needs of those less advantaged than oneself, including non-human animals, and those who will come after.

It may help you to decide what is the best course of action if you think of

yourself explaining your action to someone, alive or dead, for whom you have

or had great respect.

See

Mentor over your shoulder.

Finally, I should say that I have found some questions in ethics to

be dilemmas (having no satisfactory answer).

For example, how should a nation treat refugees?

On the one hand there is an obligation to help people in need of help, on the

other hand there is a responsibility to protect the rights and liberty of

those who will come after us.

More specifically, if we in Australia allow unrestricted access to refugees,

as would seem to be the kind action, no matter what their beliefs and ideals,

do we risk beliefs such as Islam becoming entrenched and eventually a threat

to all Australians' right to live as they chose?

| |

|

This section added 2021/03/09

|

|

Minimising one's consumption also minimises one's impact on our shared environment. Minimising our impact on the environment is essential if we are not to seriously damage our shared planet.

| |

Our tiny mobile house

|

|---|

| While many people our age bought huge camper vans or caravans worth tens of thousands of dollars and weighing tonnes, we bought this tent trailer for $3,000. The whole thing, trailer and all, weighs about 400kg.

We have since decided that we don't need the annex; by leaving it behind we can save about 13kg and by not erecting it we can save a quarter of an hour of setting up time.

|

|

|

|

|

|

The mobile tiny house folded up for the road.

A Honda Jazz has towed it many thousands of kilometres and several times over the Great Dividing Range with no problems, and uses about 7 litres of petrol per 100km while towing.

|

|

I think my wife and I have to some extent practiced minimalism for many years. For example, when we moved from Adelaide to Crystal Brook we bought a run-down and partly renovated hundred year old house for about a quarter of the typical house price of the time. So we didn't need to saddle ourselves with a mortgage that would take many years to pay off. We fixed up the old house over a decade or more and extended it when our kids were growing up. As much as we needed; no more.

But it was a program on Netflix by Joshua Fields Millburn and Ryan Nicodemus that put the name to Minimalism for us and moved me to write this section.

Joshua and Ryan argued that everyone can be happier if they downsize their houses, minimise consumption and the collection of unnecessary 'stuff'. The more you consume the more you have to work to pay off the costs of your consumption and the more stressful is your life.

Very relevant to minimalism in this sense is the tiny-house movement.

This has been a reaction to the huge and continually growing cost of buying a home - often involving the taking on of a mortgage that will take 30 years or more to pay off.

People in the past had, and people in third world countries have, much smaller and simpler houses. People in the West have been saddling themselves with bigger and bigger houses that come with bigger and bigger debts.

We've also been unknowingly involved in this; we have a shack where we spend quite a bit of our time. The living area is 36 square metres (although there is also a cellar).

Our cars have also been minimalist. Since our kids have grown up and left home we've had, consecutively, a Mazda 121 and two Honda Jazzes. When the kids were at home we had a Toyota Corona. All of these cars were the smallest that were practicable for our needs.

As I've noted elsewhere on these pages, increasing income beyond a level sufficient for covering our needs does not increase happiness. Joshua and Ryan argued that having more than enough actually reduces our satisfaction with our lives.

Of course, apart from the mental benefits that come from living minimally, we must have saved a lot of money over the years, well over a hundred thousand dollars I would think.